Although Edwardian invasion-scare fiction was written by people from a range of backgrounds, the genre’s authors can be neatly divided in two, between civilians on the one hand and military/naval personnel on the other. These opposing groups formed an unusual dynamic. As Michael Matin has explored, armed forces professionals often accused their civilian counterparts of “potentially catastrophic failures of imagination”. Oblivious to the hardships and suffering of modern warfare thanks to several centuries of sea-girt security, Britain and the British are accused in these works of over-confidence. Yet ironically, the imaginations of these expert contributors often operated “within tightly circumscribed limits.” Hamstrung by the “antitechnological cult of the offensive”, these professional speculators regularly offered far less accurate images of modern warfare than their civilian rivals.”[1]

Various scholars have attempted to explain this strange dynamic, in which the experts falter and the amateurs succeed. In Imagining Future War, Antulio Echevarria points to the challenges of assessing the short-term effects of technological change. Authors from the armed forces tend to focus “on the immediate future in an attempt to solve specific problems, usually of a tactical or technological nature.”[2] The amateur visionaries of early science fiction, by contrast, were far less temporally and thematically shackled. Falling primarily into the latter category, Echevarria suggests that the civilian authors of invasion literature made little effort “to ground…forecasts in actual events, or to verify apparent trends.”[3] Crucially, both armed forces professionals and amateur writers used the future “as a means rather than an end”, aiming to shape contemporary military strategy and society through speculative, often opportunistic novels.[4]

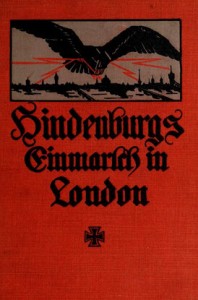

This final point is particularly important. Edwardian invasion narratives, in my view, are best understood as contemporary records rather than speculative strategic treatise. One example of the genre that aptly illustrates this point is The New Battle of Dorking (1900). This is one of several unimaginatively-named works that directly referenced George Chesney’s ground-breaking short-story The Battle of Dorking (1871). It was written by Frederic Maude, a Colonel in the Royal Engineers and prolific military historian. Maude wrote a series of strategic analyses of the Napoleonic period, including The Leipzig Campaign (1908) and The Jena Campaign (1905). He also wrote several tactical studies, such as ‘Military Training and Modern Weapons’ (Contemporary Review, 1900).

Maude was clearly more qualified than most to speculate on the future of conflict. It is curious to note, therefore, that The New Battle of Dorking offers very little in the way of accurate speculation. Maude’s basic premise, as he set out in the work’s introduction, was thus:

“There are three months in every year – July, August, September – during which the French Army is fit for immediate warfare. And every year during these months there is a constantly recurrent probability of a surprise raid on London by the 120,000 men whom they could without difficulty put on board ship, land in England, and march to within a dozen miles of London in less than three days…”[5]

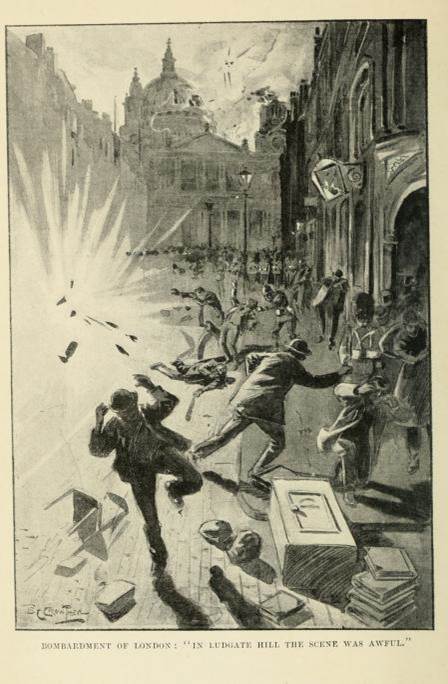

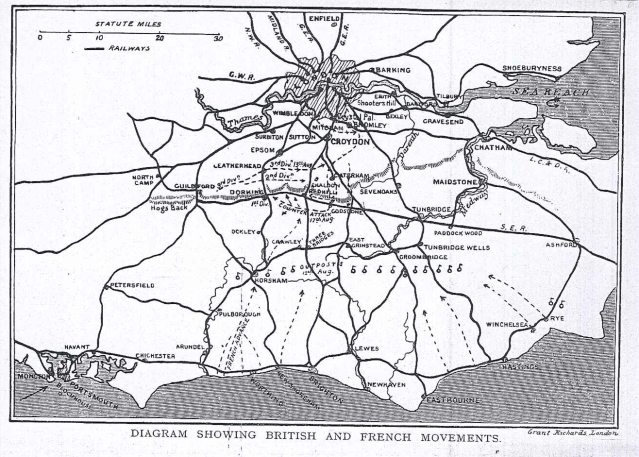

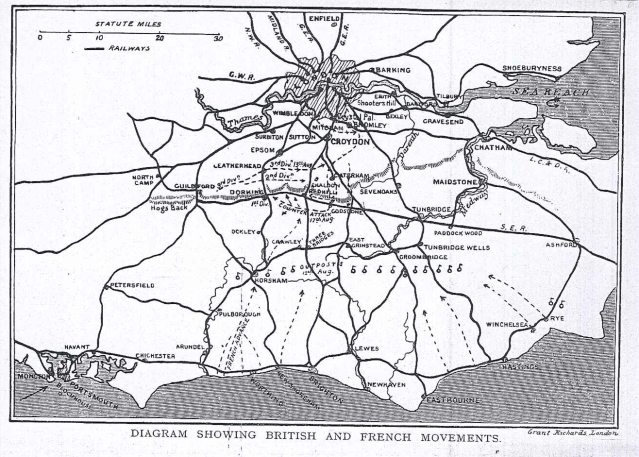

Though accepting that such a raid was hardly guaranteed success, Maude argued that “The French have everything to gain and little to lose if they make the attempt”. This, of course, is exactly what occurs in the novel. After a torpedo attack on Portsmouth Dockyard, the French land troops at Rye, Hastings, Eastbourne and Worthing. With the Navy on naval manoeuvres off the Irish Coast, and the majority of Regulars fighting in South Africa, the situation initially looks bleak. Yet the French invasion is defeated in less than a week. With the French advance into London halted at Shooters Hill, and a crushing victory won at Chaldon Downs, the final battle naturally takes place at Dorking, where the remaining French forces are convincing routed by a roughshod body of reservists and volunteers.

‘Diagram showing British and French movements’, The New Battle of Dorking (1900)

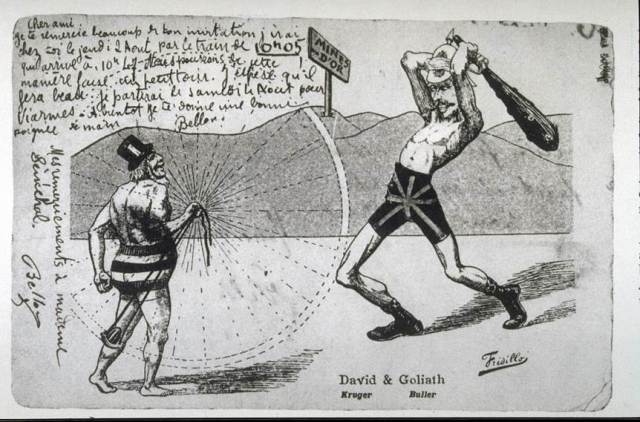

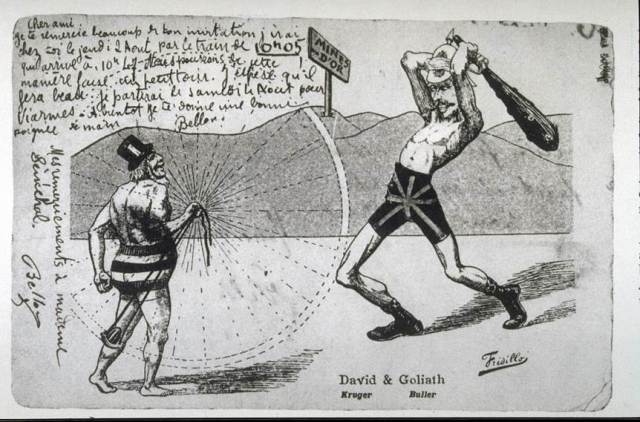

Why, then, had the military historian Maude produced such an unconvincing, disconnected narrative of future-war? I would argue that accurate prophesy was not the primary motivation behind The New Battle of Dorking. A far more important influence on the work was the contemporary debate over the concept of physical deterioration, set in motion by the disastrous South African War. Beginning in October 1899, the conflict was initially marked by a series of catastrophic British military defeats (the worst of which took place during the infamous ‘Black Week’). By the war’s end in mid-1902, it had cost 22,000 British lives, more than £200 million, and required an army of 450,000 to defeat an ill-equipped enemy.[6] Despite eventual victory, Britain’s reputation as the predominant global power had been significantly undermined. Within Britain itself, moreover, the war triggered a deep and lengthy period of introspection. One popular explanation for this poor performance concerned the health of Regular Army applicants. Though this debate reached its peak several years later through the Inter-Departmental Report on Physical Deterioration, these social Darwinist anxieties had developed into a prominent national discourse by the early months of 1900. In a representative letter to The Saturday Review entitled ‘Is England Decadent?’, compulsory military service was touted as the answer to the physical health question: “If we are afraid to rouse people to self-discipline, and to the stern performance of civic obligations, decadence sooner or later will meet us.”[7]

‘David and Goliath, Kruger and Buller’ (1900), University of California

Yet in The New Battle of Dorking we have an outspoken refutation of degeneration fears. Maude goes out of his way to praise the physical and mental qualities of the British forces. Describing an engagement at Guilford, the officer narrator describes “the quite excellent order, discipline, and the smart bearing of the men generally”. “I still felt a thrill of pride”, he continues, “in the sterling qualities of my countrymen. There were few if any loafers in the streets, and those there seemed quiet and resolute”. Turning crude Darwinism to his own ends, Maude christens the men “the survivors of the fittest”. Though accepting that Britain faced major military challenges, he “could not believe that we were as a race really degenerating. It was the fault of our training. Given a sufficient spur and properly led, our men were capable of anything.” Later in the novel, as the British troops sought to retake Bromley, the patchwork force of Volunteers and Reservists “assaulted with an irresistible courage that, under the circumstances, disciplined troops could not have excelled.” The French enemy, by contrast, were “without the moral stamina to stand up to serious reverses, or the physical strength to endure fatigue. Their discipline was the discipline of fear, not of reasoned intelligence”. Britain’s civilians, too, are far superior to their French equivalents. Addressing a crowd at Portsmouth shortly after the outbreak of war, the narrator referred disparagingly to the Paris Commune, and implored to those assembled, “Don’t lose your heads and riot, as the French mob would do”.[8]

The significance of Maude’s novel, then, is not in its vision of future warfare, but in its critique of degeneration anxieties. While the genre more broadly was not completely bereft of strategic insight, speculation on the nature of modern warfare was rarely the primary consideration, or focus, of invasion literature authors. Instead of seeking to understand the shortfalls of these military visions, then, historians should arguably seek to contextualise such fiction in the cultural, political, and military history of the pre-1914 period.

—

This post is based on a research paper originally delivered as part of the First World War Research Group Seminar Series at the Defence Studies Department, King’s College London.

—

[1] A. Michael Matin, ‘The Creativity of War Planners: Armed Forces Professionals and the Pre-1914 British Invasion-Scare Genre’, ELH, 78.4 (2011), p. 818-822.

[2] A. J. Echevarria II, Imagining Future War: The West’s Technological Revolution and Visions of Wars to Come, 1880-1914 (Westport CA: Praeger Security International, 2007), pp. 96-98.

[3] Ibid., p. 49.

[4] Ibid., xv.

[5] F. N. Maude, The New Battle of Dorking (London: G. Richards, 1900).

[6] D. Lowry, ‘Not Just a ‘Tea-Time War’’, in The South African War Reappraised, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 2.

[7] ‘Is England Decadent?’, Saturday Review, 89.2306 (1900), p. 14.

[8] Maude, The New Battle of Dorking.